Help! I can’t breathe; I feel I may suffocate under the delusion that I can still find a way to be perfect.

If you can relate to the above sentence, even a little, keep reading…

Are we so worried about being perfect that we drink ourselves into alcoholism because of the lofty expectations that we impose on ourselves?

I’m not sure anyone could provide a definitive answer to the above question, but after twenty-nine years in recovery, I can tell you that the theme of perfectionism crops up over and over again in recovery rooms. Does perfectionism give birth to alcoholism? It’s entirely possible that perfectionism feeds the drinking because at the bottom of all that perfectionism is usually someone who doesn’t feel okay in their own skin—the person who can’t breathe because their chest feels tight and they can’t divorce that feeling of aloneness that’s enveloped them since childhood; perfectionism is about the masks we wear in hopes that no one will notice that underneath the polished exterior is a drowning soul desperate for some relief from the voice in their head that says do more, be more, do just one more thing and then everything will be perfect—but the truth is that nothing in life is ever perfect, nor should it be. We’re human; we’re incapable of perfection.

Perfectionism can show up as low self-esteem, and maybe it starts for some in their teenage years when life is confusing for everyone and hardly anyone has the skills to look within, so we look outward toward other things or people to help soothe the fear, anxiety, and any other emotion that is too damn difficult to deal with at the moment.

I’ve talked with scads of women, most of them now in recovery, who were quick to say that for many of them, underneath their battle with alcoholism was an unrelenting perfectionist; underneath thoughts of suicide and self-harm was a pitiless perfectionist. In order to believe that there’s not a link between perfectionism and alcoholism—we’d have to be willing to overlook a whole chorus of voices. Perhaps it goes back to our first interactions with others when we were children: perhaps too many of us had a critical parent or a sibling who bullied us or some other person in our life who was cruel; perhaps the need to be perfect stems from issues of control, because the environment where we grew up was so out of control that our subconscious minds demanded some order, and if everything looked perfect, we would feel safe; perhaps perfectionism is birthed when we enter the world with our own unique DNA and we find that we’ve morphed into neurotic perfectionists through no fault of our own or of our parents, but because that’s how we are wired and that’s who we are. Most perfectionists will continue to run themselves ragged until they are so worn out by their perfectionism that they decide to do something about it and change, or not.

Perhaps for some, the inclination toward perfectionism started in high school where instead of learning to love and accept ourselves, we turned to alcohol because that’s what our peers did and if we wanted to fit in…but we realized something about alcohol that other’s may have missed: alcohol worked for us in a way that felt magical! Awww the mystical elixir that numbed insecurities, changed the way we felt and gave us the courage we needed to attempt to grow-up and navigate this crazy world that has no roadmap, and we had to admit we had no clue what we were doing. In fact, after a few drinks, we felt invincible—that gnawing sense of inadequacies, or the feeling of not belonging or not knowing what the hell we were doing all but disappeared, with a drink.

As women, do we hold ourselves to unobtainable standards? Do we strive to be the perfect daughter, sister, girlfriend, wife, mother, employee, and friend? Pick a role—but somewhere in that quest to be the best, we realized we failed to hold up to our own high standards, and as everyone eventually does, we came to the place in our lives where we realized that life is imperfect; that we’re fallible; that no matter how beautiful we are or how well we beat our bodies into submission that there will be boyfriends or SO’s who will still cheat and those pants will always be too tight because we’ll never be a size 6 or an 8 again; that there are no perfect parents, and that our own mother’s had their own baggage and some of their resentments leaked out sideways onto her innocent children; that our sisters and friends betrayed us; that no one cared as much about our accomplishments or our failures as we did, and that the world can be complicated and cruel if we allowed it to be complicated and cruel.

Is Fear the Driving Factor Behind Perfectionism?

Let’s use the example of a perfectionist who underneath, is riddled with fear. As I point out in Raising the Bottom:

Then there’s the gal who fears she will never have enough security, stature, or contentment, so she grabs for more and more to help her feel secure. Her expectations are off the charts—she demands the outcome of her choice, and when she doesn’t get it, you will pay. She hasn’t learned how to ask for what she needs, and instead she expects you to intuitively know what she needs and then provide, tout de suite!

She also believes that she deserves to have attention, all the accolades, all the help, and all of your time and energy. She wants the best house, the best car, the best jewelry, the best job, the best spouse, the best kids. Enough will never be enough. She takes the disease of more to a whole new stratosphere. No one can live up to her impossible standards. Eventually exhausted, even she can’t keep up with her high standards.”

Why Do We Beat Ourselves Up?

When there’s a lack of self-love, we do things that aren’t loving. We want things in life that we think will change the way we feel, and maybe for a few minutes it works, but it always comes back to being an inside job. If we don’t like who we are inside, there is nothing, absolutely nothing we can acquire that will fix our inner worlds. The only solution is to do the work and slog through those difficult feelings, and work that sh*t out!

Perfectionism can also start in childhood with our mothers. I know my mother was focused on appearances. She never left the house without her hair, makeup and clothes all just so. I found a picture of her when I was a kid with my siblings. I can’t remember where were were, but there’s my mother in a beautiful blue dress and matching handbag, but you can see that she’s zoned out on valium. She’s there, but she’s not there.

We can dress up the outsides any way we to look perfect, but the eyes tell the tale and our hearts know the truth. Sometimes—misery cannot be disguised, and in the picture, my mother looks miserable. Of course, my mother went down the road of addiction. Did her perfectionism bleed onto her daughters? In many ways, I think it did. We all had eating disorders, alcoholism/addiction issues. As I write in the introduction of Raising the Bottom:

The women in my family bled all over each other; when we weren’t hemorrhaging fear, we spent our time looking for an out. None of us know how to feel and deal. Our one thought was escape, and the answer to every triumph or sorrow was: Drink this. Swallow that.”

It wasn’t until I found recovery that I was able to look at it and examine if I had been afflicted with the need to be perfect, and with much work and reflection, I came to realize that perfectionism wasn’t the greatest hurdle I had to surmount. Sure, it lurked in the background, but I knew early on in my recovery that I wanted to sever whatever tentacles perfectionism had attached to me. It became far more important that I was free rather than, perfect. I loved that in recovery I was allowed to be human, and that means fallible: It was okay to be a total screw off some days, leave the house a mess, not get that promotion, have a kid that doesn’t make the soccer team or wasn’t the stand out winner on the debate team, and guess what—nothing awful happens! When you realize that people are all focused on their own stuff, their own families, their own worries, and that no one is looking at you—it helps to let go of that self-centeredness that plagues a perfectionists life.

“And now that you don’t have to be perfect, you can be good.”

– John Steinbeck

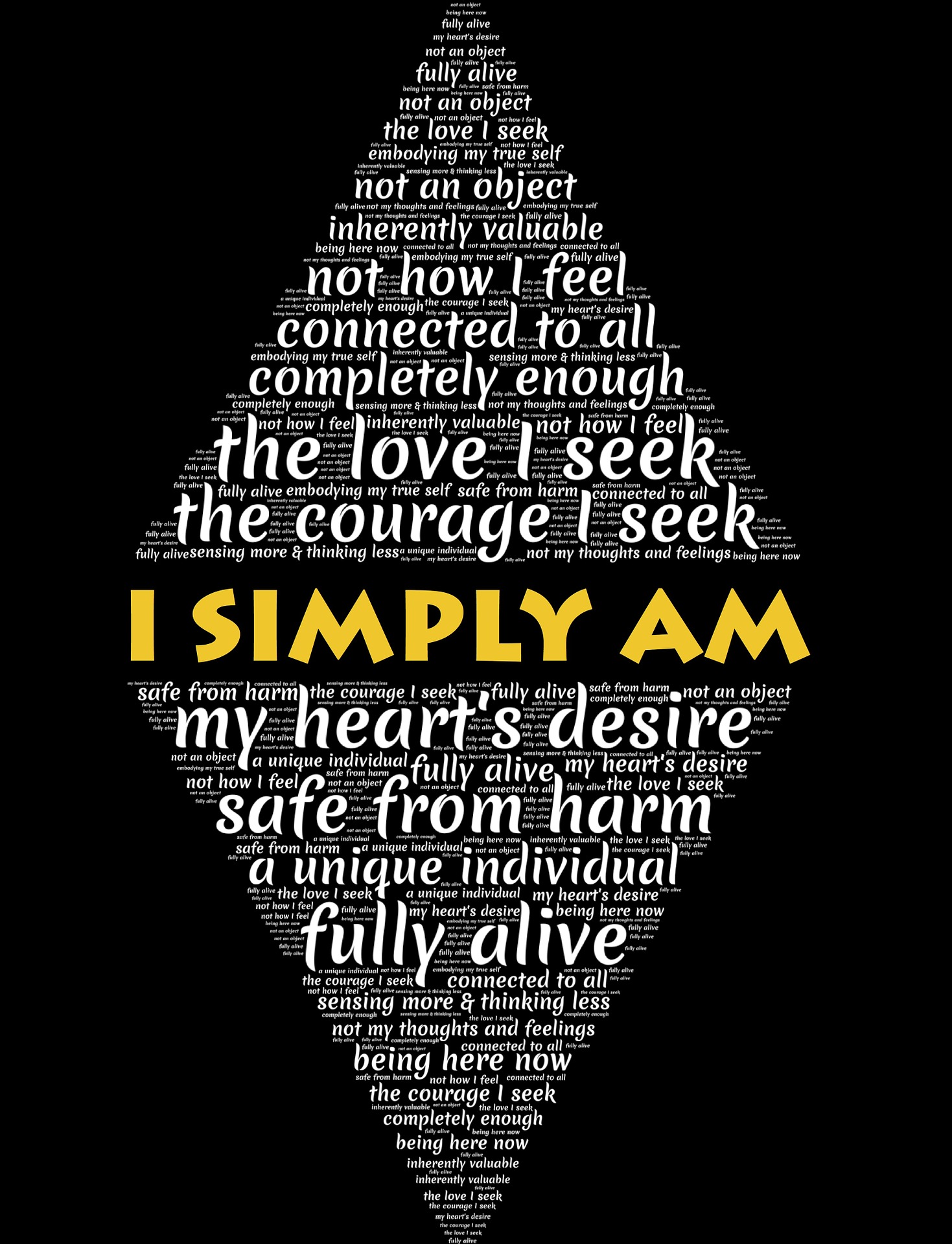

To recover from perfectionism is to fall in love with yourself and to realize that you don’t have to be perfect to be loved. You don’t have to be accomplished in order to be loved. When you get to the place where you can love yourself and none of the outside trappings matter anymore—you’ll know that you’re well on your way to self-love, and that also translates to mean—you now have a quiet mind and a peaceful heart.

In summary:

Forget about who you think others want you to be

Every single time—opt for the best version of yourself

Understand that you can’t take a triangle or a hexagon and make it any more of a triangle or hexagon than it already is. You don’t have to reinvent what’s already perfectly flawed, and perfectly you.

Lisa is the author of the multi-award winning book, Raising the Bottom: Mindful Choices in a Drinking Culture. After short stints where she trained polo horses, worked as a flight attendant, hairdresser, and bartender, she revamped her life and settled in as a registered nurse. For the past twenty-nine years has worked with hundreds of women to overcome alcoholism, live better lives and become better parents. She was prompted to write Raising the Bottom when she realized after twenty plus years of working in hospitals, that doctors and traditional healthcare offer few solutions to women with addiction issues. You can start reading for free on Amazon. Follow her on Twitter @LBoucherAuthor and Instagram